USE OF MINI-IMPLANTS AND COMPOSITE RESIN FOR ATROPHIC MANDIBLES

BACKGROUND OF IMPLANTS

Edentulism increases with age. It is estimated that 20% of the population will increase to be at least 65 years of age during the next 50 years.1 In 1965, life expectancy was 65 years of age. By 2001, life expectancy had grown to 85 years of age.2 A 65 year old female in good health has a 50% chance of living to the age of 85.3 It is estimated that 26% over 65 and 44% of those over 75 are completely edentulous in both arches.4 Partially edentulous seniors older than 65 have lost an average of 18% teeth.5 Today’s retirees have a net worth of more than one quarter of a million dollars which is three times the net worth of working families 35 to 45 years of age.6 In the early part of 2002, standard sized implants had been on the market nearly six decades. Beginning in Sweden they were slowly introduced to the dentists of North America. The efficacy of dental implant treatment has been proven and well-accepted by the profession, 7-9 and should be considered an important part of managing the care of a patient with missing teeth.10 These early implants averaged 4 mm in diameter and were constructed out of a titanium alloy. Research had shown that the rough titanium surface and the bone would adhere to each other. The titanium would “osseointegrate” with the bone. Removing an implant was often so difficult that the surrounding bone would fracture before the titanium separated from the bone. The connection between bone and titanium was judged to be stronger than the bone itself. The implants provided excellent support for oral prosthetics. This opened the door to having artificial teeth rigidly connected to the bone. It gave patients who had lost their natural teeth another opportunity to have rigidly fixed teeth in their mouths. Before implants, edentulous patients got dentures which were very mobile and unstable plastic teeth which moved unpredictably as the patient chewed food. Dentures have always been a dismal substitute to natural teeth. Today, it’s often standard procedure to remove the dentures from residents of nursing homes and have them drink nutritional milkshakes rather than allow them to chew their food. But, with teeth anchored by implants, chewing food, laughing, muscle size and tone returned to the delight of the patients. Consequently, the general consensus was that fixed dentures using implants were an unqualified success both mechanically, nutritionally, and emotionally for the patients.

AIM OF THIS ARTICLE

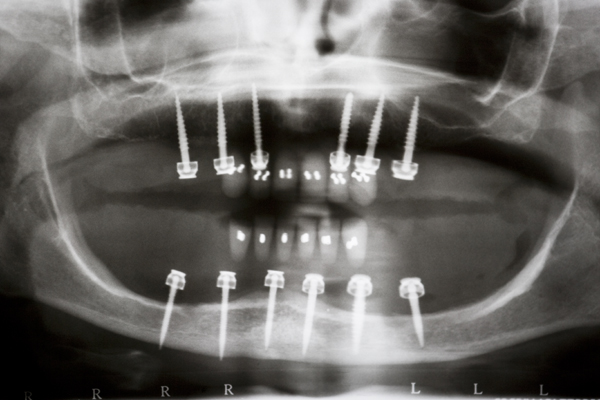

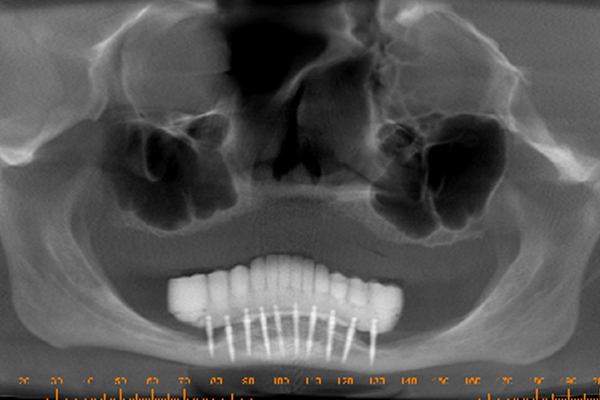

This article introduces a technique which can be used by any dental implant surgeon who have patients with advanced atrophy of the mandible. Considering all of the edentulous patients, only 1/3 have sufficient bone to support standard sized implants. In a small percentage of cases, mini-implants connected to O-rings can provide minimal stability. This can be seen in Figures 1 and 2. This article introduces the unique benefits of small diameter implants (mini-implants, < 3.0 mm. D) and nano-hybrid composite resin teeth for the restoration of the 2/3 of edentulous patients who have insufficient bone to support standard-sized implants. The only option for this group is full dentures.

BEGINNINGS: MINI-IMPLANTS AND O-RINGS

Over time, implants changed shape. Specifically, the implants less than 3.00 mm in diameter were known as “mini-implants”. Balkin et. al found that the bone around immediately loaded 3M’s MDI mini-implants appeared histologically to be integrated to the surface of the implant at the light microscope level.11 Simon et. al12,13 have shown that MDI mini-implants do integrate despite immediate loading in their study involving removal torque. Simon et.al have also shown that the percentage of implant-to-bone contact of the MDI mini-implants was comparable to that of standard-sized implants which suggested the use of mini-implants in more definitive treatments over the long run. Bulard and Vance reported average failure rates of 8.8% which suggested that mini-implants can be effective devices for long term denture stabilization.14

DENTURE SUPPORTED BY MINI-IMPLANTS

Shatkin et. al reported an overall implant survival rate of 94% in a five-year study following 2,514 MDI mini-implants under fixed (N=1278) and removable (N=1236) prostheses.15 A popular technique was to place mini-implants in the symphysis and attach them to dentures via O-rings in the anterior third of the denture. There was no posterior support preventing the dentures from pivoting on the implants and creating destructive lateral loads when the patient chewed on the posterior teeth. The relentless rocking back and forth would sometimes loosen the implants. Surgeons were called upon to remove the failing implants and had very little exposure to the mini-implants which were successful. To improve the overall success of the mini-implants, one could place them in the posterior of the mandible where they could provide tooth support and prevent pivoting of the denture. Having a Cone Beam Computerized Tomography x-ray (CBCT) in the next room gives the surgeon the benefit to check implant placement during surgery. I was able to take patients who had been refused implants due to lack of bone, and place the 2.0 mm. mini-implants in the atrophic bone. I treated all patients with bone atrophy and never refused to attempt placement of the mini-implants.

MINI-IMPLANTS IN THE POSTERIOR MANDIBLE

By placing mini-implants in the posterior of mandibles, I was providing the needed support for the O-ring dentures. There was an immediate improvement in mini-implant successes. Placing mini-implants in the posterior of atrophic mandibles is still controversial. Patients having this surgery performed signed informed consents explaining the risks and complications of this new type of surgery. As many dentists still limited their implant placement to the mandibular symphysis, there was a continued belief in a lower than normal success rate. Dentists admitted to a reluctance to use the mini-implants for fear of dental specialists criticizing their judgment in using them. I began placing mini-implants distal to the mental foramen in order to eliminate the lack of support under the distal free-end saddles of O-ring retained dentures. As mentioned, the rates of success for the mini-implants increased. The good news was having the implants immediately underneath and perpendicular to masticatory forces proved to be an unqualified success. The bad news was the frequent parasthesia due to impingement of the inferior alveolar nerve. However, when patients were given the opportunity to alleviate the parasthesia by having the implants removed, but losing their fixed teeth, they refused. The benefits of the fixed teeth outweighed the liability of numbness. What a paradigm shift for the dentist! It was but a few decades ago that parasthesia would have automatically triggered a malpractice suit.

ELIMINATING THE O-RINGS

The weakest link in the denture-implant-O-ring system was the O-rings. As patients popped out their dentures and replaced them, the O-rings began to wear out. Re-inserting the dentures became the most challenging step. Aligning all of the implants with the appropriate O-rings was very challenging. Failure to do so would rip or gouge the O-rings which accelerated their wearing out. Wanda M. was nearly blind and wore an O-ring retained set of dentures. While inserting her lower denture, Figure 3., she dropped it and broke it. Her eyesight, which was so critical to aligning the denture, was compromised. A new approach was needed and with Wanda’s full consent, I reshaped her denture to eliminate the flanges which filled the buccal vestibule and projected into the floor of the mouth. The intaglio surface of her denture was shaped and polished to be convex with the O-ring keepers barely held in by the acrylic. I removed the O-rings from the inside of the keepers. Using dual cure composite resin cement, I bonded Wanda’s denture to her healthy lower implants. I discovered that even though the O-rings may seem passive when the denture was properly seated, they weren’t. They still exerted a mild but perceptible pressure on the implants. When Wanda’s teeth were cemented, the resin cement flowed gently and there were no pressures exerted on the implants. It was a “perfect” fit. See Figure 4. There weren’t any micro-pressures like those produced by the O-rings. She called me four hours later to say the diffuse and barely perceptible sensations in her mandible were gone. Having left 2 mm between the denture and her soft tissues, she was able to maintain outstanding oral hygiene. But most importantly, Wanda commented that her evening meal was the most enjoyable meal she had had since wearing dentures. Wanda continued to compliment me and my solution to her dilemma. She nurtured my desire to try this procedure again on other patients.

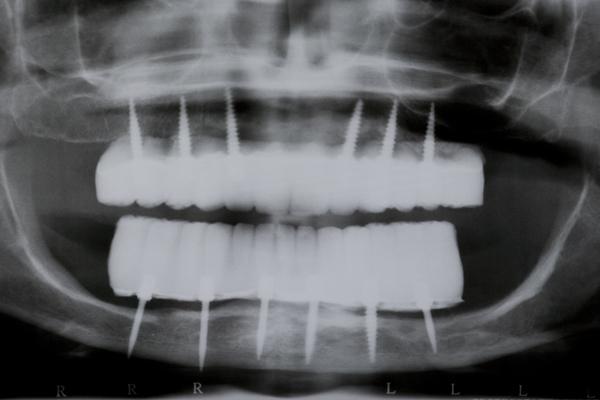

INTRODUCTION OF NANO-HYBRID COMPOSITE RESIN

I approached Judy Y. who already had worn a mandibular O-ring supported denture for nearly a year. After discussing the pros and cons, she agreed to have teeth cemented onto her mini-implants. I made an alginate impression of her denture in her mouth, made a flexible plastic mold of the stone model, and used it to create an arch of teeth made out of nano-hybrid composite resin. I had always been fascinated by how the composite resin could be manipulated into the shape of a tooth and then turned into rock by merely using a curing light for 20 seconds. I used eight tubes (approx. 40 gm.) of composite resin to create a full arch of teeth for Judy. When I removed her O-ring denture and bonded the composite resin teeth in her mouth with a dual-cure composite resin cement, the first words out of her mouth were, “My teeth have disappeared!” I later theorized that the dual cure composite resin cement allowed for a completely passive fit of the teeth. Absent were the pressures from the O-rings which were always present with her O-ring denture. “A perfect fit”, This was the genesis of “FixtTeeth”. It was a procedure whereby mini-implants provided the sole means of support to composite resin teeth. See Figures 5 and 6. The connection between the mini-implants and the composite resin was a composite resin, dual-cure cement making the teeth connected rigidly to the implants. I now had a rigid structure connecting the implants like planks connecting fence posts. I had created a titanium/composite resin structure in Judy’s mouth that was not only more comfortable than her O-ring denture, but it was substantially stronger. Now the implants functioned in harmony dissipating masticatory forces uniformly into the bone. In turn the bone was stimulated and grew denser thus increasing the entire system strength of bone/titanium/composite. It eliminated the metal O-ring keepers allowing for smoother, narrower connections between titanium and composite which was even more comfortable and more hygienic for the patient. I now had a rigid structure connecting the implants like planks connecting fence posts. I had created a titanium/composite resin structure in Judy’s mouth that was not only more comfortable than her O-ring denture, but it was substantially stronger. Now the implants functioned in harmony dissipating masticatory forces uniformly into the bone. In turn the bone was stimulated and grew denser thus increasing the entire system strength of bone/titanium/composite. It eliminated the metal O-ring keepers allowing for smoother, narrower connections between titanium and composite which was even more comfortable and more hygienic for the patient.

COMBINING COMPOSITE RESIN AND MINI-IMPLANTS TO MAKE A FIXED PROSTHESIS

TO MAKE A FIXED PROSTHESIS

FixtTeeth falls outside the box for most dentists. Some of the harshest critics of FixTeeth have never placed mini-implants. They haven’t made teeth out of composite resin. The paradigm shifts are simply too big and too many for the average implant dentist. It’s going to take a while before they understand and accept the advantages of mini-implants. For example, if an alveolar ridge’s buccal-lingual bone thickness is 3 mm., it would provide at least 0.5 mm. of hard cortical bone around the neck of a 2.0 mm. D implant. The buccal and lingual cortical plates would be left intact wherein the mini-implants were >80% successful. Any standard-sized implant (3.0 mm. D. or larger) would be impossible to use. There would be no facial or lingual bone. In addition, 18 mm. long mini-implants were more likely to encounter internal cortical bone just due to their length. This would provide the golden “bi-cortical” stabilization endorsed by early implantology. Then the success rate would top 96%. So when I encountered a true knife-edged ridge, I would use a round bur and reduce the bone to get a 3 mm. starting platform. Then I’d use the sharply-pointed, gently tapered, 1.2 mm. pilot drill to track into the softer cancellous bone between the two cortical plates. Once I was into cancellous bone, I’d switch to a 1.1 mm. spiral drill and plunge to a depth of 18 mm. In the maxilla, I usually encountered the cortical bone of the floor of the nose or one of the interior walls of the maxillary sinus. In the mandible, it was usually the cortical bone of the inferior border of the mandible. Now the 2.0 x 18 mm. implant would have its neck surrounded by the two cortical plates of the alveolar ridge and its tip would be imbedded in the hard cortical bone of the maxillary sinus walls or the inferior border of the mandible. I found a niche for the mini-implants where standard-sized implants couldn’t be used: the knife-edged ridge. Big implants are not always a better choice when dealing with atrophied bone.

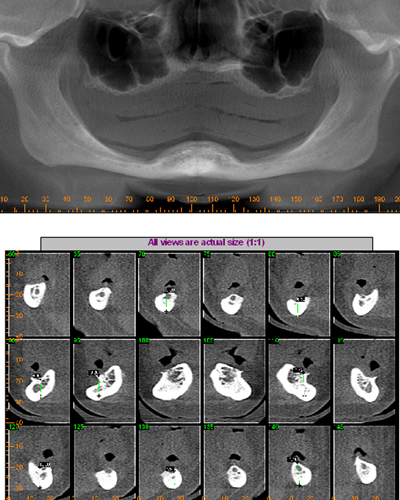

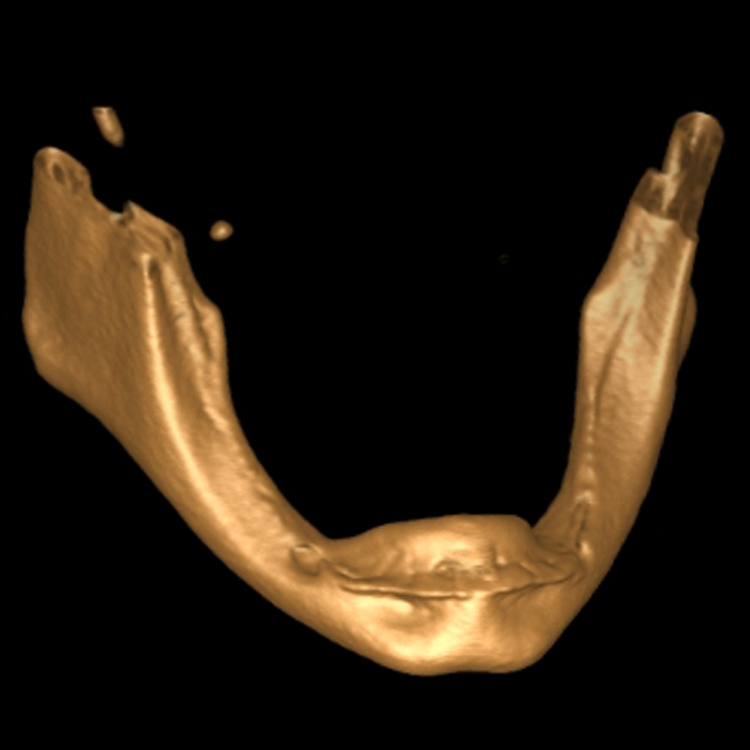

SEVERELY ATROPHIC MANDIBLE

A 57 year old female patient suffered with a lower denture due to lack of bone. See Figure 7. It had atrophied to the point that the lower denture had little or no support near the crest of the mandible. See Figure 8. Atrophy was so severe that the inferior alveolar nerve canal was at the crest of the mandibular ridge. The 3-D image below gives a good view of the lack of bone. Figure 9 shows the mini-implants in place with the composite resin teeth attached. Figure 10 shows the hygienic gap between the teeth and the soft tissues.

The support of the implants allows a 300-800% increase in masticatory forces. The masseter begins to return to its pre-extraction size. It obliterates the gap between the prosthesis and the soft tissues. Oral hygiene spirals downward because it’s nearly impossible to get the bristles of a toothbrush under the prosthesis. Now the prosthesis is buried under the masseter. The tissue is a swollen, inflamed, bleeding mass of trouble.

LENGTHENING THE MASSETER

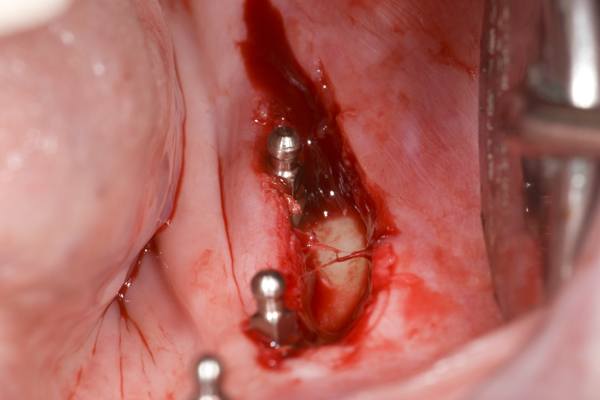

The surgery needed begins with a full thickness incision surgical incision from the retromolar pad to the crest of the ridge above mental foramen. The incision should pass immediately to the lateral side of each implant and go through the periosteum. The object is to sever all attachments of the masseter to the bone and genio-glossus muscle. Figure 11 shows the initial incision.

The periosteum is separated from the bone approximately 3 mm.to the facial from the incision and every implant. Gently grasping the elevated periosteum with tissue forceps in one hand, use a scalpel in the other hand to tease away the masseter muscle right above the periosteum. This exposes an additional 5 mm. of periosteum. At the retromolar pad, begin a split-thickness flap in the masseter traveling all the way to the other end if the initial incision. Use a sharp pair of scissors to puncture and spread the masseter muscle and continue facially creating an envelope at least 20 mm. wide. Stay in the masseter and close to the bone, but don’t pierce the periosteum. By staying close to the periosteum you will avoid damage to any vital structures. The masseter has now been “elongated”. Its reduced insertion will be the last 5 mm. of the mandibular lateral surface just above the inferior border of the mandible.

This surgery is the old vestibule extension so popular decades ago. It was commonly used to increase exposure of the mandible. The thinking was a denture would have attached non-mobile tissue for support. But this attached tissue would be very thin which caused great pain if a small seed were to find its way underneath the denture. The vestibule extension was modestly successful at reducing the amount of “denture float”. After exposing a large envelope of masseter muscle, tissue conditioner or perio packing is placed into the buccal vestibule keeping the masseter exposed during the healing stage. Anchoring of the tissue conditioner is accomplished by pushing it in between the implants and underneath the prosthesis. The objective is to nurture a new layer of mucosa over the exposed masseter. In addition, new attached tissue is formed on the exposed periosteum and bone next to the implants. This new attached tissue at the implants will be the key to maintaining good oral hygiene. The masseter will enlarge through use, but it won’t compromise the small space next to the implants. The increased length of the masseter will facilitate an increase in vertical dimension. The prosthesis can be fabricated to compensate for the overall bone loss and restore the lost dimension to the lower third of the face. This has a profound positive effect on the patient’s countenance.

MINI-IMPLANTS AND THE INFERIOR ALVEOLAR NERVE CANAL

I remember one patient in particular who had a 7 mm. high mandible and I was successful in placing eight mini-implants and building her some teeth. The bad news was there wasn’t much bone and I went straight through the middle of the inferior alveolar nerve canal which resulted in parasthesia. The good news was the mandible was solid D1 “cue-ball” bone for strength and the resulting parasthesia abated over a period of 14 months. The pilot drill for the mini’s is 1.2 mm in diameter which doesn’t macerate the nerve when performing the osteotomy as it probably does doing standard-sized implants. I attended Gordon Christensen’s first lecture on mini-implants in Scottsdale. At lunch I consulted with Dr. Christensen and showed him among other things the photos of this inferior alveolar canal “bulls-eye”. I told him of the resulting parasthesia abating within a year. With a quizzical expression, Dr. Christensen wondered out loud, ”Do you think the nerve just rolls up and out of the way?” Of course, I thought. The slippery myelin sheath prevents direct piercing of the nerve by the pointed pilot drill tip used with mini’s. Since mini’s have a tapered pointed tip, they miss piercing the myelin sheath of the nerve upon insertion. But, fully inserted, they compress the nerve against the inner wall of the nerve canal. Then, the pressure parasthesia is ameliorated by the slow remodeling of the nerve canal bone allowing the nerve to resume normal shape and function.

MINI-IMPLANTS STIMULATING CORTICAL BONE GROWTH

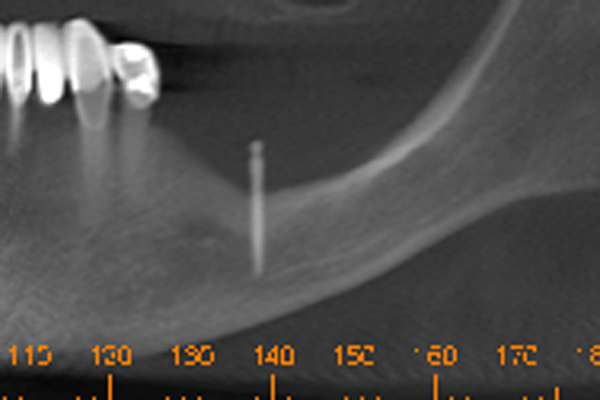

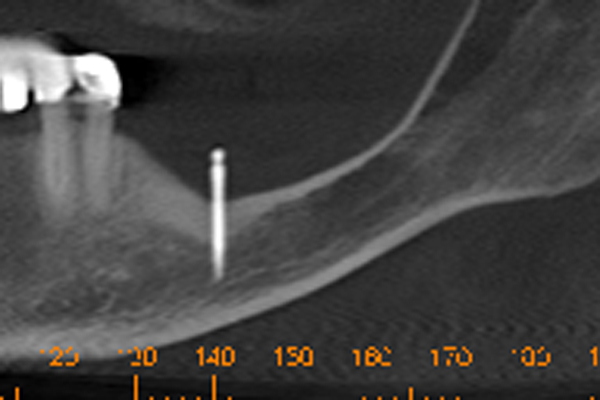

This brings me to an exciting discovery that I made with a 60+ year old female wearing a bilateral free-end partial. She wanted to supplement the partial’s clasps with mini’s and O-rings. I placed one mini at #19, see Figure 12, to support the saddle which replaced all teeth distal to #22. Three mini’s were placed under the right saddle which replaced all teeth distal to #27. After five years she returned stating the lower left hurt sometimes. Inspection revealed a mini which sounded like a steel pipe when tapped with the handle of my mirror. It was NOT loose. I asked her to lift her tongue to the roof of her mouth. When she did so, the solitary mini-implant on the left disappeared into a hole fully six millimeters deep. I was stunned and for a moment could not believe my eyes. I then realized that the masseter had hypertrophied due to vigorous use. When it flexed, it became enormous as muscle does when exercised. Her intermittent soreness occurred when she flexed the masseter and inserted the partial. She would perforate the masseter between the mini implant and the O-ring. It would be sore until she reinserted the partial in a relaxed mode and then the pain disappeared for weeks at a time. The other surprise came when I evaluated her CT scan and saw an enormous amount of cortical bone surrounding the single mini. The “exercise” not only bulked up the masseter, but caused an increase in the volume of cortical bone around the implant. See Figure 13. This can be clearly seen on her CT scan. I theorize that the mini’s act as stimulators which increase bone density just like the electro-stimulation common with spinal surgery which is used to accelerate bone healing. So, instead of always bone grafting, maybe the mini’s could stimulate existing bone to become denser and more plentiful. The categorical expectation of having 1/10 mm. crestal bone loss per year around the neck of the implant is not necessarily true. It could mean that the surgeon chose too big of an implant leaving too little bone for adequate support.

COMPLICATIONS

Chips, cracks and some implant failures occured in <48% of the cases. Most resin failures were caused by its low tensile strength. Sometimes it was caused by implants loosening and not integrating with the bone. In either case, repairing the composite in the mouth was much easier to repair compared to porcelain. It was not necessary to cut metal and it was possible to bond composite to freshly cut composite all in a matter of hours. This would be almost impossible with porcelain. There were a few patients who were “ice crunchers” and pathologic bruxers who chipped, cracked, and broke the resin, but none required more than a quick repair or a simple duplication of teeth. When an implant failed, the resin was cut above the implant, the failed implant was lifted out, and new composite resin was bonded back where the original composite had been cut. Sometimes another implant could be placed which replaced the failing one. As a result of "nursing" the implants through the first year, the bone increases in density around the implants. Furthermore, an arch of composite resin teeth could then be bonded to a metal substructure. This addressed the composite’s weakness of low tensile strength which further strengthened the system of bone/titanium/composite. The longer the implants lasted, the stronger the bone became. Parasthesia was not an uncommon complaint. It was carefully explained to each patient before the procedure that partial or complete parasthesia was a complication of FixtTeeth. Accordingly, each patient had signed an informed consent acknowleding this. Fortunately, numbness usually resolved spontaneously within six to eighteen months in over 50% of the cases.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Over 450 cases of FixtTeeth have been done since 2006 utilizing in excess of 6500 mini-implants. No patient was refused treatment due to lack of bone. Some mandibles were less than 8 mm. thick. Implant success exceeded 85% overall. It is clear that abundant bone surrounding large implants would be ideal. In such circumstances, mini-implants would not be the first choice. But, in circumstances where little bone exists, the smaller implants conserve bone which promises a greater chance of success. The other factor about FixtTeeth which might be critcized is the use of nano-hybrid composite resin for teeth. Including a metal substructure for the composite solves the low tensile strength problems. Also, a metal substructure supporting traditional denture acrylic and denture teeth could be equally successful. Resultantly, FixtTeeth can always be presented as an adjunct to dentures when existing bone is too scarce for standard-sized implants. FixtTeeth can also be presented as a less expensive alternative to grafting and standard-sized implants. The cost for a full arch of FixtTeeth using mini-implants and composite resin is approximately 30% the cost of the alternative choice which uses $600 implants and costs $50-$60K. Mini-implants in severely atrophic mandibles is a “win-win” endeavor. The patient gets the heretofore impossible: a complete set of fixed teeth. The professional satisfaction derived from such a success is very high. FixtTeeth can therefore be an option for anyone facing lengthy, expensive bone grafting or extensive restorative costs. The profession now finally has a solution that is effective, life changing, and relatively inexpensive to help the edentulous patient with extensive bone resorbtion. It is time for patients with atrophic mandibles and maxillae to be given the choice of mini-implants and composite resin.

REFERENCES

1. Murdock SH,Hoque MN. Current patterns and future trends in the population of the United States: Implications for dentists and the dental profession in the twenty-first century. J Am Coll Dent 1998;65(4):29-35

2. Hellmich N. Extra weight shaves years off lives. USA Today. Jan 7, 2003:A.01

3. Dychtwald K. Age wave: The challenge and opportunities of an aging America. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1968

4. A profile of older Americans, Washington, DC, 1993, American Association of Retired Persons

5. Bloom B, Gift HC, Jack SS. Dental Services and Oral Health: United States, 1989. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1992; 10(183).

6. Aschenbrener CA. The future is in the present: The impact of generations. J Am Coll Dent 1998;65(4):23-29

7. Adell R, Lekholm U, Rockler B, Brånemark PL. A 15-year study of osseointegrated implants in the treatment of edentulous jaw. Int J Oral Surg 1981;10(6):387-416

8. Brånemark PL, Hansson BO, Adell R, et al. Osseointegrated implants in the treatment of the edentulous jaw: Experience from a 10-year period. Scan J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1977;16:1-132

9. Jemt T, Lekholm, Adell R. Osseointegrated implants in the treatment of partially edentulous patients: A preliminary study on 876 consecutively placed fixtures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Impl 1989;4(3):211-217

10. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs. Dental endosseous implants: An update. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135(1)

11. Balkin BE, Steflik DE, Naval F. Mini-dental implants insertion with the auto advance technique for ongoing applications. J Oral Impl 2001;27(1):32-37.

12. Simon H Caputo A. Removal torque of immediately loaded transitional endosseous implants in human subjects. Int J Oral Maxillofac Impl 2001;17(6):839-845.

13. Froum SJ, Simon H, Cho SC, et al. Histologic evaluation of bone-implant contact of immediately loaded transitional implants after 6 to 27 months. Int J Oral Maxillofac Impl 2005;20(1):54-60

14. Bulard RA, Vance JB. Multi-clinic evaluation using mini-dental implants for long term denture stabilization: A preliminary biometric evaluation. Compend Cont Educ Dent 2005;26(12):892-897.

15. Shatkin TE, Shatkin S, Oppenheimer BD, Oppenheimer AJ. Mini dental implants placed over a five-year period. Compend Cont Educ Dent 2007;28(2):92-99.